Pärt: Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten

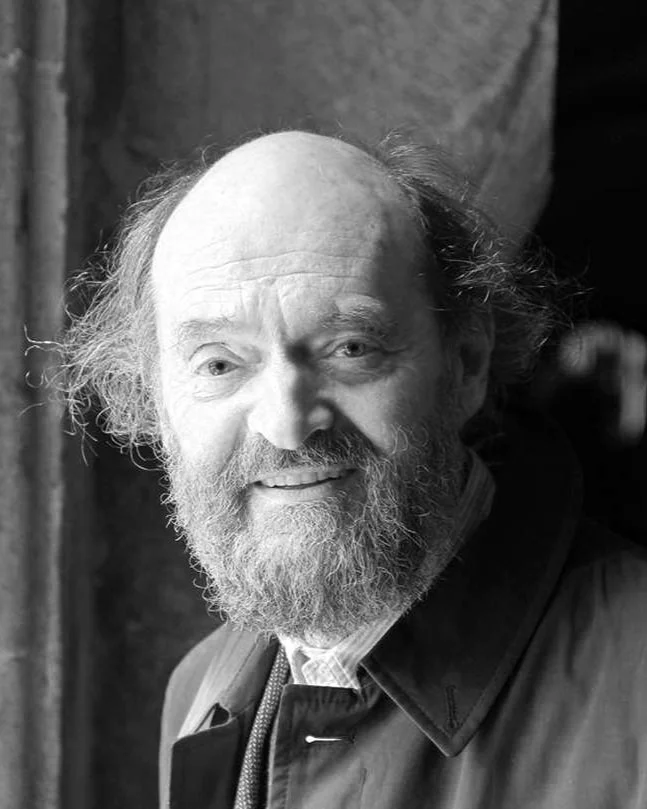

Composer Arvo Pärt (1935 - )

by Chris Chris Vaneman

In the Soviet Union once, I spoke with a monk and asked him how, as a composer, Once can improve oneself. He answered me by saying he knew of no solution. I told him that I also wrote prayers, and set prayers and the texts of psalms to music, and that perhaps this would be of help to me as a composer. To this he said, “No, you are wrong. All the prayers have already been written. You don’t need to write any more. Everything has been prepared. Now you have to prepare yourself.”

Thus writes Arvo Pärt, in explaining his own approach to music and life; if it sounds a little mystical to you, let’s just say that you’re not alone. Pärt has for many years been driven by his intense and very personal Christian faith, forging his own path with a unique and most individual approach to his art. Over the course of decades he has won the respect of critics and academics and, more important, the deep affection of audiences: from 2011 to 2018 he was the world’s most-performed living composer, yielding that position in 2019 to no less a figure than John Williams.

Pärt is a citizen and the best-known export of Estonia, the tiny country on the Baltic Sea that between 1940 and 1991 was subsumed by the USSR. He spent much of the 1960’s battling Soviet censors because he insisted on using a Serialist approach to composition, turning out music in the hyper-mathematical, dissonant style introduced by Arnold Schoenberg. A conversion to Orthodox Christianity in 1972 led to a four-year period of artistic silence, and when he returned to composition in 1976 it was with music that could hardly have been more different. Gone were dissonance and extreme complexity, and in their place was a meditative simplicity akin to the chant of monks. The Soviet authorities weren’t much friendlier, however, since he was open about his music’s explicitly religious inspiration, and he shortly defected to Germany. After Estonia regained its independence he finally moved back, and he remains his country’s most famous citizen.

Begun immediately after the illustrious British composer Britten’s death in December of 1976, the Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten was among the works Pärt broke his silence with in 1977. It uses the very simplest of musical materials – an A Minor chord and a descending A minor scale (aka, the white notes on the piano keyboard) to enormously powerful effect.

That, in a sense, is what you need to know about this piece. I could instead have told you this story, which in another way tells you all you need to know: In the Fall of 2001, my wife and our friend Scott Robbins were young music professors a few years into their Converse careers. On September 12 they both had scheduled classes full of shocked and grieving students. Both of them – independently and without being aware of the other’s plans – brought to class their own CD’s of the Cantus, played the piece for their students, and, after sitting in silence for some minutes, sent everybody home.