Elgar: Nimrod

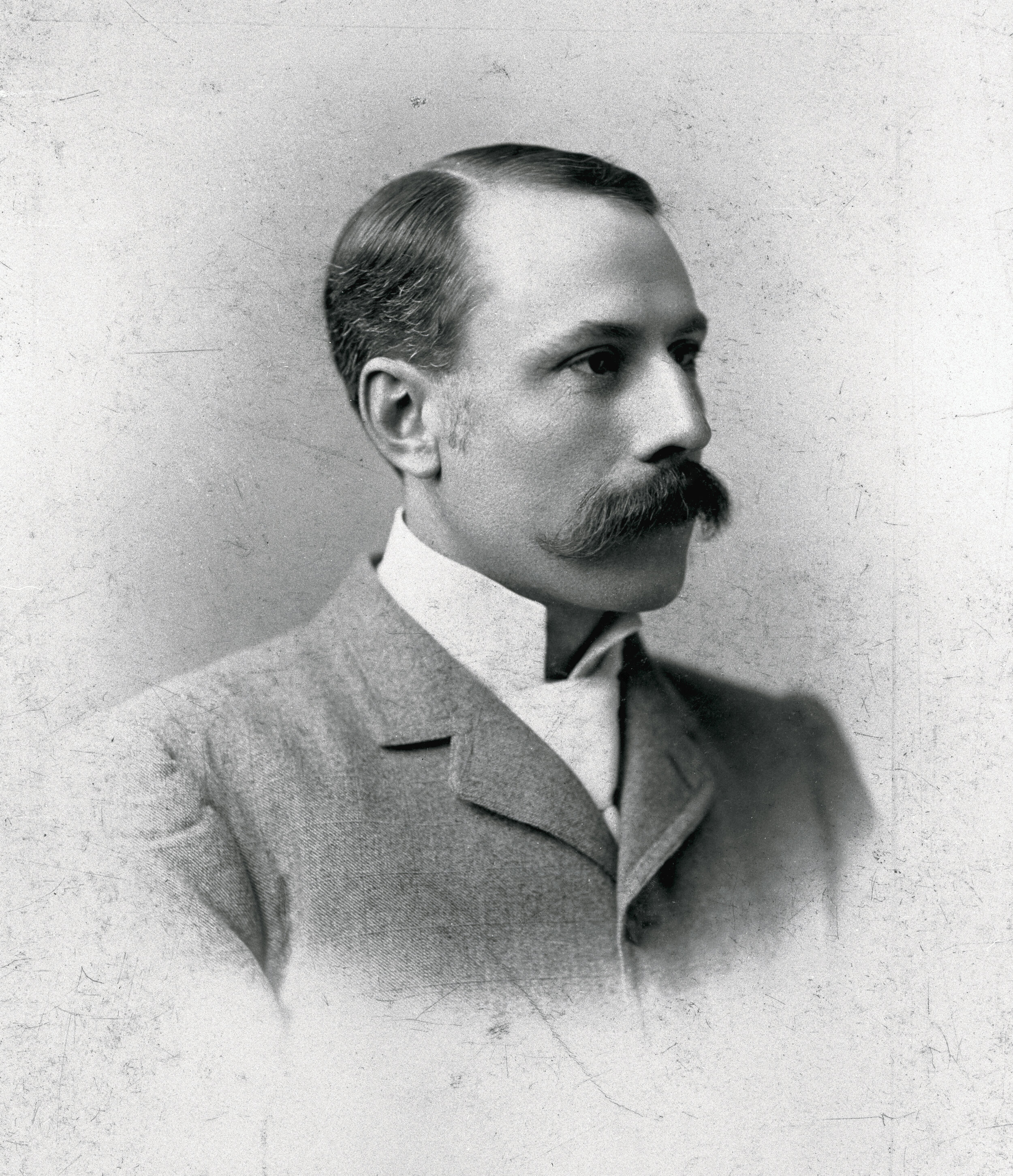

Photographs of Sir Edward Elgar present what appears to be the absolute archetype of the Edwardian English ruling class: a vast, rounded dome of a forehead, an imperious brow, a hawklike nose, and a mustache of a size and impressiveness that it seems to defy the laws of both human anatomy and gravity. And the utter ubiquity of his Pomp & Circumstance March No. 1 at graduation ceremonies – the most formal activities in many Americans’ lives – reinforces his image as the human epitome of the British empire at its most dominant.

But, as is so often the case with these things, our preconception is almost entirely wrong. Elgar was Roman Catholic, the son of a humble small-town organist, and never studied at a prestigious London conservatory. Most of his music, far from being pompous or stuffy, displays an emotionalism and formal innovation more akin to Wagner than to, say, Sir Arthur Sullivan. And when he did marry into the upper class, the family of his new father-in-law – a retired Major-General – was so scandalized that they disinherited and cut off relations with the couple.

Elgar’s eventual recognition by the British and then worldwide audiences didn’t come till he was 42, with the 1899 premiere of the Enigma Variations. The Variations’ title reflects their unique form: they’re a series of variations, each dedicated to a friend or acquaintance, on a theme that is never actually heard. And in fact Elgar never did reveal what the theme was, which has meant that musical detectives have busied themselves for over a century trying to identify it.

While the composer’s wife and female friends are depicted in lovely variations, the piece’s lushest and most romantic music is reserved for his publisher, August Jaeger. Jaeger had shown faith in and encouraged the composer for years as he labored in obscurity, and he was rewarded with “Nimrod,” among the most purely beautiful music for orchestra ever created. (Nimrod was the mighty hunter of the Book of Genesis; Jaeger, as Spartanburg’s many German-speakers already know, translates as “Hunter.”) “Nimrod’s” unusually expansive melody is cushioned by plush harmonies and seems to flow impossibly slowly – time itself seems to stop as we bask in its golden glow.

See a performance

Hear The Program

Chris Vaneman is the Dean of the School of the Arts and Associate Professor of Flute at Converse University. Chris frequently leads the Spartanburg Philharmonic pre-concert lecture series “Classical Conversations,” and occasionally performs as a substitute flutist in the orchestra.